|

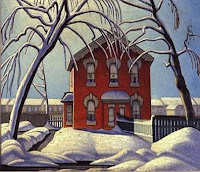

| Lawren Harris, "Red House" |

Beginning in those years, I have adored the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the CBC. In the 70s, it helped me acquire a cache of Canadian lore, as well as an appreciation of a Canadian point of view. Back then, while still in my intellectually formative years, I listened to its a.m. programing from morning to night. (For a couple of those years I was working on my theology degree at McGill’s Faculty of Religious Studies.)

Thanks to the Internet and streaming audio, I once again am listening a lot to CBC programing throughout the day.

I’m glad that our own National Public Radio has adopted some Canadian programs. Perhaps you’ve listened to one called IDEAS that is a potpourri offering of cultural and intellectual topics. It’s simply outstanding.

This program, Ideas, has become the venue for one of the major Canadian intellectual events, the yearly Massey lectures. These lectures were first offered 50 years ago by the CBC. The lecturers have been distinguished, including Martin Luther King, Jr. who delivered the five talks in 1967.

The 2011 Massey Lectures were delivered in November by Adam Gopnik, writer, essayist, and commentator, well known for his work in The New Yorker Magazine. Gopnik, born in 1956 in Philadelphia, was raised in Montreal where his parents taught at McGill. He titled his lectures, Winter: Five Windows on the Season. Those lectures have been published as a book.

The central theme of Gopnik’s Winter lectures involves a modern state of mind. Modern means an era from the beginning of the19th century through the end of the twentieth century. He says:

A mind of winter, a mind for winter, not sensing the season of loss and life, and with them hope of life and divinity, but ready to respond to it as a positive, and even purifying, presence of something else – the beautiful and peaceful, yes, but also the mysterious, strange, the sublime – is a modern taste.

Now, modern I mean in the sense that the loftier kinds of historians of ideas like to use this term, to mean not just right here and now but also the longer historical period that begins sometime around the end of the 18th century, breathes fire from the twin dragons of the French and Industrial Revolutions, and then still blows cinder-breath into at least the end of the 20th century, drawing deep with twin lungs of applied science and mass culture. An age of growth and an age of death, the age in which, for the first time in both Europe and America, more people are warmer than they had been before, and in which fewer people had faith in God – an age when, at last, the nays had it.

Gopnik contends that in 200 years of a modern era, winter had ceased to be a season to be endured and tested (fated by God) and had become a season of metaphor (for human imagination to find meaning). He labels this a Romantic vision.

Gopnik further says:

Loving winter can seem, in a very long perspective of history, perverse. Of all the natural metaphors of existence that we have – light versus dark, sweet against bitter – none seems more natural than the opposition of the seasons: warmth against cold, spring against fall, and above all, summer against winter. Human beings make metaphors as naturally as bees make honey, and one of the most natural metaphors we make is of winter as time of abandonment and retreat. The oldest metaphors for winter are all metaphors of loss. In classical myth, winter is Demeter's sorrow at the abduction of her daughter by death. In almost every other European mythology it is the same: winter is hard and summer soft, as surely as sweet wine is better than bitter lees.

The taste for winter, a love for winter vistas – a belief that they are as beautiful and seductive in their own way, and as essential to the human spirit and human soul as any summer scene – is a part of modern condition. Wallace Stevens, in his poem the “Snowman,” called this new feeling a mind for winter, and he identified it with our new acceptance of a world without illusions, our readiness to live in a world that might have meaning but that doesn't have God.

And Gopnik summarizes: My subject is the new feelings winter has provoked in men and women of those modern times: fear, joy, exhilaration, magnetic appeal and mysterious attraction. Since to be modern is to let imagination and invention do a lot of the work once done by tradition and ritual, winter is in some ways the most modern season—the season defined by absences (of warmth, leaf, blossom) that can be imagined as stranger presences (of secrets, roots, hearth).

I invoke Adam Gopnik’s lectures and their central theme, because my UU colleagues have liberally engaged in finding the meaning of the Winter Season we’re about to enter, particularly during the high tide of mid-Twentieth Century humanism. These colleagues, as have I, have looked through the Winter window, perhaps etched with hoarfrost crystals, and have had their religious imaginations respond to the waterscape they encountered. Adam Gopnik’s understandings have made me realize that UUs have made Winter, not only a season of the mind, but even more a season of meaning.

This meaning-making is no little undertaking/accomplishment, especially in the absence of God, a mark of the modern point of view. This morning I invite you to repose in the reflections of a few favorite UU meaning-makers.

|

| Lionel Fitzgerald |

Here are familiar words by Greta Crosby, one of my 20th century colleagues and pioneering female minister:

Let us not wish away the winter. It is a season to itself, not simply the way to spring.

When trees rest, growing no leaves, gathering no light, they let in sky and trace themselves delicately against dawns and sunsets.

The clarity and brilliance of the winter sky delight. The loom of fog softens edges, lulls the eyes and ears of the quiet, awakens by risk the unquiet. A low dark sky can snow, emblem of individuality, liberality, and aggregate power. Snow invites to contemplation and to sport.

Winter is a table set with ice and starlight.

Winter dark tends to warm light: fire and candles; winter cold to hugs and huddles; winter want to gifts and sharing; winter danger to visions, plans, and common endeavoring – and the zest of narrow escapes; winter tedium to merrymaking.

Let us therefore praise winter, rich in beauty, challenge, and pregnant negativities.

|

| A. Y. Jackson |

[This was followed by readings by Henry David Thoreau, Kenneth L. Patton, and Max Coots.]

One area which usually gets forgotten during the winter season is the patio but you could get a patio heater so that you could still get to use this area.

ReplyDelete